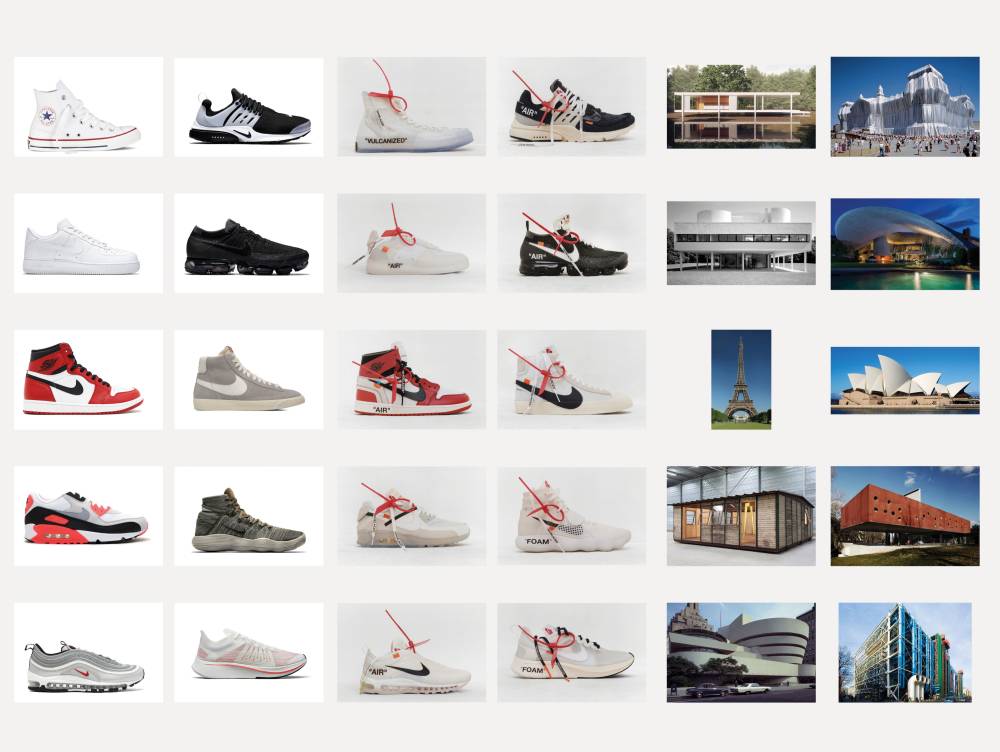

Specific numbers and dates hold particular significance to everyone. If you ask any sneaker head or pop-culture obsessed millennial what comes to mind when they hear the number TEN, or what excites them most about November 2017, they will likely mention the much anticipated release of Nike’s latest collaboration with culture icon and Off-White creative director, Virgil Abloh. Abloh took on the heavy task of reimagining ten iconic Nike sneakers in a limited edition capsule called “The Ten”. The collection, which includes classic Nike styles originally designed for running and basketball, is split into two sets, the “revealing” pack and the “ghosting” pack, grouped largely based on their design technique and materiality.

Abloh’s formal training in architecture played an important role in the recognition process associated with his manipulation and reworking of already progressive sneaker designs. Comparing the original styles to their latest iterations, a patterned dialogue emerges on modern thought and artistic intervention. Abloh’s formal manipulations manifest themselves by way of objective insignias, novel materials and the act of deconstructing and rebuilding. Examining his process further, it makes most sense to compare each sneaker design not to their original incarnation, but to their architectural counterpart.

Abloh’s transformation of the Nike-owned Converse Chuck Taylor All-Star into an almost entirely translucent shell atop a “vulcanized” blue, rubber sole, is reminiscent in its modern use of materials and exposed structural elements to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. The streamlined look of van de Rohe’s 1951 architectural masterpiece in Plano, Illinois, made up simply of a roof and floor planes, and enclosed by sheets of glass, deceives visual logic and assumption with all joining elements hidden. Similarly, the thick sole and exposed seams in the upper silhouette of Abloh’s Chuck Taylor All-Star coupled with its transparent shell, has also compromised conventional logic for the sake of design ingenuity.

Converse Chuck Taylor All-Star

Original

Converse Chuck Taylor All-Star

The TEN

Farnsworth House

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

The off-white hue, translucent bottom and re-stitched swoosh of Abloh’s re-imagined Air Force 1 is a minimalist interpretation of Nike’s most iconic sneaker design of all time. Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s Villa Savoye in Poissy, France, is arguably the formal icon of modernist architecture. Elevated from earth, looking to almost float atop ground-level supports, the simplicity of Villa Savoye’s white, skin-like façade and set back, horizontal row of ribbon windows, bares significant structural and aesthetic similarities to the translucent sole and all white exterior of Abloh’s Air Force 1.

Nike Air Force 1 Low

Original

Nike Air Force 1 Low

The TEN

Villa Savoye

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret

Nike’s Air Jordan was created in 1984 for Basketball player Michael Jordan. The Air Jordan 1 was released to the market in 1985 in a number of color ways, but none more iconic that the style rendered in black, red and white, the team colors of Jordan’s Chicago Bulls. Since 1985, the footwear design has taken on countless iterations, always maintaining it position as a symbol of sportswear and modernity. Virgil’s subtle modifications of the quintessential basketball sneaker include verbiage spelling “AIR” across the sneaker’s sole, a large black swoosh reattached with electric blue thread, and contrasting black stitching around the entirety of the sneaker’s colorful shell. The only architectural equivalent comparable to one of the most recognized sneaker designs in history is the most iconic structure in the world, the Eiffel Tower. Built a century before the Air Jordan was introduced, construction on the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889, just in time for the World’s Fair. Like the Jordan sneaker, the Eiffel Tower’s namesake, Gustav Eiffel whose company built the tower, was imperative to the structure’s design and completion. Stylistically, the exposed black stitching of Virgil’s Air Jordan 1 bares resemblance to the framework of the wrought iron structure.

Nike Air Jordan 1

Original

Nike Air Jordan 1

The TEN

Eiffel Tower

Engineer: Gustav Eiffel

Abloh’s redesign of Nike’s Air Max 90 was the most stylistically and structurally involved of the ten modernized styles. The bright colors and complex layering technique of the original sneaker were maintained in its latest iteration with Virgil’s Air Max 90 being the most colorful of the group, blending off-white and blue with light yellow and hints of orange. The designer conserved the cut-and-sewn technique of the original style, dismantling the sneaker’s layered pieces and reconstructing them in a different order, making Nike’s trademark swoosh more prominent in the process. The building and ideas most closely linked to Abloh’s design approach concerning the Air Max 90 are the homes of Jean Prouvé, specifically the 8x8 Demountable House of 1945. Like the layers of Nike’s Air Max 90, Prouvé’s homes provide variability through standardized elements such as moveable partition walls, rolling doors and skylights. These dismountable structures can be deconstructed, moved and rebuilt in a variety of combinations and often include varied materials and colorful elements, proving them the ideal architectural counterparts to Virgil’s re-mastering of Nike’s iconic Air Max sneaker design.

Nike Air Max 90

Original

Nike Air Max 90

The TEN

8x8 Demountable House

Jean Prouvé

Nike’s Air Max 97 received the “ghosting” treatment by Abloh who transformed the original style known for its prominent, fluid lines, 3m reflective piping and minimal branding, into a translucent shell accessorized by an extended black swoosh and prominent block lettering. The shoe’s monochromatic, white shell makes the rigid lines of the original style appear almost invisible, giving Abloh’s rendition a clean, seamless look recalling the continuous spiral of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. When the structure made its debut on the corner of 5th Avenue and 89th street in 1959, the circular scheme of the cylindrical building was a vast departure from the rigid geometry of modern architecture at the time. The gentle slope of the museum’s galleries lining the interior edges of the building give its white façade a seamless look, besides a thin, black ribbon of windows tracing the museum’s galleries, similar in decoration to the prominent hints of black on Vrigil’s Air Max 97.

Nike Air Max 97

Original

Nike Air Max 97

The TEN

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Frank Lloyd Wright

Virgil’s redesign of Nike’s Air Presto sneaker involved strictly ornamental adjustments, an exterior renovation, if you will, on a classic. While structural elements of the Air Presto went primarily untouched, a number of changes were made to the sneaker’s shell; the trademark Nike swoosh was relocated from the toe and sewn to the exterior of the shoe, Abloh’s objective verbiage was plastered across the sneaker’s heel, with “AIR” written in large white letters, and the materiality of the shoe was significantly altered through the addition of mesh wrapped around the entirety of the sneaker’s shell. Abloh’s external renovations are similar in approach and technique to artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrapping of the Reichstag in Belin, Germany. In 1995, personal and professional partners, Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped the entirety of Berlin’s Reichstag for 14 days, a project which took 24 years to be realized. In keeping with their artistic tradition, the duo used over 100,000 square meters of thick woven polypropylene fabric with aluminum, and 15.6 kilometers of blue polypropylene rope. While the artistic act in question does not qualify as architecture in the traditional sense, its absolute reliance on an existing edifice and preservation of the building’s structural elements recall immense similarity to Abloh’s reimaging of the Air Presto Sneaker.

Nike Air Presto

Original

Nike Air Presto

The TEN

Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

The flyknit shell and Air Max cushion of Nike’s AirVapor Max give the original sneaker design a sleek, futuristic aesthetic. Virgil’s reimagining of the innovative style includes a contrasting and reattached Swoosh, text on the interior and exterior sides of the sneaker’s shell and an enlarged foam tongue. Abloh’s additive design elements, which maintain the sneaker’s futuristic look, coupled with its unique combination of materials, embody the ideals of architect John Lautner’s trademark aesthetic, particularly concerning the house he designed for comedian Bob Hope and his wife Dolores in Palm Springs, California. Key characteristics of this sprawling, curved structure completed in 1979 include its sloping roof, floor to ceiling windows, interior circular skylight and Lautner’s prominent mix of materials such as glass and poured concrete.

Nike Air VaporMax

Original

Nike Air VaporMax

The TEN

Bob Hope House

John Lautner

The traditional 1970s design of Nike’s Blazer Mid has made the shoe a classic for over 40 years. The sneaker’s thick sole and empowering swoosh are native design elements to the retro style, which has gone through a number of iterations over the past four decades. Virgil’s Blazer Mid bears a lower-than-normal jet-black swoosh which creeps onto the shoe’s upper sole. The white and off-white fabrication of Abloh’s sneaker coupled with its ornamental features are of a similar design approach and fabrication to architect Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, built in 1973. Like the minor variations of white that are present on Virgil’s sneaker design, the ornamental ‘shells’ of the Sydney Opera House feature both glossy white and a matte cream tiles, adding visual interest and complexity to the otherwise stark hue.

Nike Blazer Mid

Original

Nike Blazer Mid

The TEN

Sydney Opera House

Jørn Utzon

Nike’s React Hyperdunk 2017 is the newest Nike style to be remastered by Virgil Abloh. The sneaker’s flyknit shell and substantial React foam cushioning was whitewashed by the designer and accessorized with an elongated black swoosh and a transparent, sock dart overlay. The thick sole and dotted encasing, bare striking similarities to the simple volumes and structural complexities of Rem Koolhaas’ cantilevered home, Maison Bordeaux, in Bordeaux, France. The structure, built in 1998, fluctuates in materiality between opaque and transparent matter and provides tremendous spatial variability, akin to the performance variability offered by Nike’s flyknit material. Lastly, from a design perspective, the circular, transparent portholes of the home’s upper volume form a spotted pattern visually homogonous to the transparent, dotted top strap of Abloh’s React Hyperdunk 2017.

Nike React Hyperdunk 2017

The Original

Nike React Hyperdunk 2017

The TEN

Maison Bordeaux

Rem Koolhaas

Nike’s Zoom Vaporfly made its debut this past June as a specialized sneaker for track and field athletes. Virgil’s subtle manipulations of the high-performance style include a reconstructed, reattached swoosh and a slight re-fabrication, leaving the original sneaker’s carbon fiber plate and streamlined silhouette largely untouched. Abloh preserved the Zoom Vaporfly’s highly technical, performance elements while adding variation and ornamentation to its shell, recalling figurative similarities to the Centre Georges-Pompidou in Paris. Architects Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano completed the high-tech structure in 1977, not as a museum, but as a highly flexible centre of the arts. Rogers and Piano approached architectural ornamentation in a functional sense, exposing color-coded ‘would be’ electrical infrastructure on the exterior of the building. This unorthodox design resolution frees up a tremendous amount of internal space, allowing for greater variability in the galleries and interior space, giving the building high-performance elements akin to Nike’s Zoom Vaporfly sneaker.